copyWrite By Mark House

[email protected]

With actual newspaper documentation recognizing high school football being played in some southwest Oklahoma territorial towns as early as 1903, nothing has been found to pre-date the existence of competition within the tradition rich football community of Clinton, Oklahoma, before October 15, 1910. While game days were becoming popular at the turn of the twentieth century in southwest Oklahoma townships such as Hobart, Granite, Altus, Cordell, Blair, Olustee and even Gotebo, Mrs. Ballew of Clinton was discovered visiting her sister in Mangum while everybody who was anybody traveled to Clinton with effort to tend to various types of business matters. Instead of pursuing urgent ventures such as developing a quality football squad (sarcasm inserted here), Clinton and it's pioneering leaders seemed to be more focused on politics, religion and education along with rapid agricultural, business and railway development.

Much like a complicated double reverse criss-cross post pattern, diligent and criss-cross referenced historical data points towards 1910 as the point in time relative to when the Clinton football tradition actually began. Recognizing an unpolished beginning compared to evolutionary progress toward an established football powerhouse are two different lines of scrimmage, the following research of pigskinned data is shared for the enjoyment of Red Tornado fans of all ages. As well, it is shared as an educational and motivational enhancement for current and former fans, coaches and players to comprehend the general genesis of their historical game of the gridiron bourne and nurtured within a unique community of passionate fans represented by devoted coaches and players past, present and future.

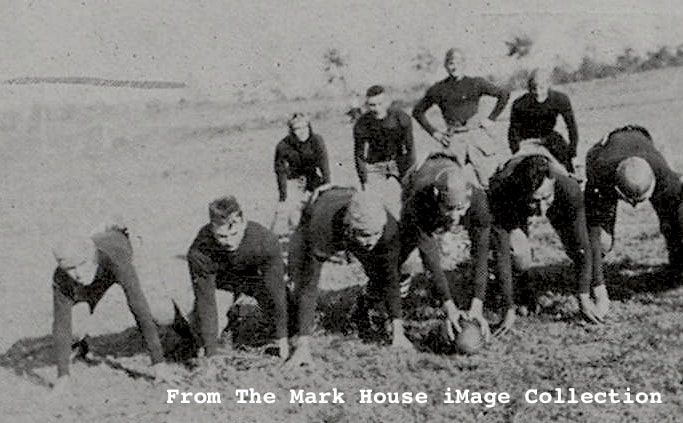

Under a cloudy and cold gray southwest Oklahoma sky, a team of gridiron trailblazers from Clinton traveled to, of all places, Sentinel, Oklahoma, for what is thought to be Clinton's inaugural rumble on the range in the Lord's year of 1910. In the previous year of 1909, research indicates Clinton High School consisted of grades 10 and 11 only (12 would not exist until 1910) and was literally made up of a minimal number of students. Considering a numerically quantitative girls to boys ratio guestimate of 3-1, no senior class before 1910, and, no trace of previous documented evidence, a theory of no football existing previous to 1910 is supported with common mathematical sensed thought processing. With a congregate of raw, farm fresh plowboys and railroaders set to receive kick from the Sentinel high school eleven, the genesis kick-off to what has now evolved into more than a century of prominent football tradition was booted into a strong southwest Sentinel breeze at exactly 4 p.m. central standard time (CST) on Saturday, October 15, 1910.

[email protected]

With actual newspaper documentation recognizing high school football being played in some southwest Oklahoma territorial towns as early as 1903, nothing has been found to pre-date the existence of competition within the tradition rich football community of Clinton, Oklahoma, before October 15, 1910. While game days were becoming popular at the turn of the twentieth century in southwest Oklahoma townships such as Hobart, Granite, Altus, Cordell, Blair, Olustee and even Gotebo, Mrs. Ballew of Clinton was discovered visiting her sister in Mangum while everybody who was anybody traveled to Clinton with effort to tend to various types of business matters. Instead of pursuing urgent ventures such as developing a quality football squad (sarcasm inserted here), Clinton and it's pioneering leaders seemed to be more focused on politics, religion and education along with rapid agricultural, business and railway development.

Much like a complicated double reverse criss-cross post pattern, diligent and criss-cross referenced historical data points towards 1910 as the point in time relative to when the Clinton football tradition actually began. Recognizing an unpolished beginning compared to evolutionary progress toward an established football powerhouse are two different lines of scrimmage, the following research of pigskinned data is shared for the enjoyment of Red Tornado fans of all ages. As well, it is shared as an educational and motivational enhancement for current and former fans, coaches and players to comprehend the general genesis of their historical game of the gridiron bourne and nurtured within a unique community of passionate fans represented by devoted coaches and players past, present and future.

Under a cloudy and cold gray southwest Oklahoma sky, a team of gridiron trailblazers from Clinton traveled to, of all places, Sentinel, Oklahoma, for what is thought to be Clinton's inaugural rumble on the range in the Lord's year of 1910. In the previous year of 1909, research indicates Clinton High School consisted of grades 10 and 11 only (12 would not exist until 1910) and was literally made up of a minimal number of students. Considering a numerically quantitative girls to boys ratio guestimate of 3-1, no senior class before 1910, and, no trace of previous documented evidence, a theory of no football existing previous to 1910 is supported with common mathematical sensed thought processing. With a congregate of raw, farm fresh plowboys and railroaders set to receive kick from the Sentinel high school eleven, the genesis kick-off to what has now evolved into more than a century of prominent football tradition was booted into a strong southwest Sentinel breeze at exactly 4 p.m. central standard time (CST) on Saturday, October 15, 1910.

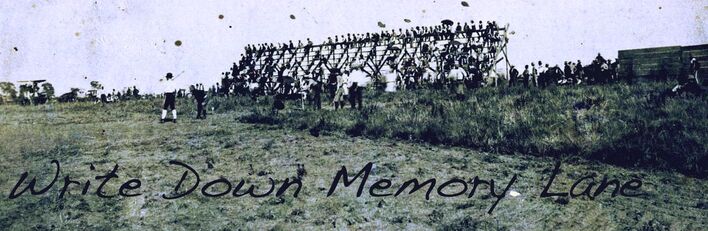

An archaic iMage of Clinton High School football (dark uniforms) captures the Red Tornadoes embattled within actual gridiron home field action just a short fifteen years after an original genesis kick off that took its place in history on October 15 in the Lord's year of 1910.

Sentinel's home town press immediately recognized the boys from Clinton as being "quick," but, it seems the Sentinel eleven were somewhat quicker in 1910. With no doubt quickness can and will get you around the right or left end for a touchdown, that is just what happened when George Cobean scored the first ever touchdown against Clinton on an end run. John D. Terry made kick for a 7-0 Sentinel lead. Unfortunately for Clinton, this first seven points was all that was needed as the gridiron pioneers could not cross goal on a brisk Saturday afternoon down in Sentinel. A final score of 33 to 0 is not a good one to report, but, for those who follow Clinton football, it is known things turn out much better at various points of time in a future filled with great players and great teams.

The Sentinel game was considered interesting and with "many points worthy of commendation." Despite victory, the crowd was small and the Sentinel boys were left indebted near fifteen dollars, hence, the value of an enthusiastic booster club should never be taken for granted. Ironically, Clinton's focus on business growth first and football second may have actually paid off in the "long run" as its gridiron tradition continues to grow while many others in southwest Oklahoma, such as Sentinel, ceased to exist quite some time ago.

Suffering from a shutout loss and with little time for the boys from Clinton to improve, Sentinel returned the favor of game as they traveled to Clinton two weeks later to participate in a contest hosted by the Clinton eleven. This first home game itself was played under difficult conditions. The Clinton gridiron was hastily constructed in a wheat stubbled field freshly raked over within just a few hours before kick-off. The dry and sandy soil was near two inches deep. To grasp a true scope of the environment, readers can visualize a field running north and south with a strong north wind blasting mini sand drifts around the pointed and dry wheat stubble upon the red dirt western Oklahoma plains. With football officially kicking off in Clinton at 2 p.m. on October 29, 1910, both Sentinel and Clinton fumbled a few times as neither team scored in the first quarter of play. The Clinton defense had at least displayed some improvement within the two week span between these inaugural and antiquated contests.

In the second quarter, Sentinel took command by scoring touchdowns on a line buck and a criss-cross fake run. Bystanders, evidently from Sentinel, declared the game "remarkable" and the final score ended with another shutout of Clinton's eleven by a reported score of 26-0. With a criss cross check of facts, the 26-0 score revealed by the Sentinel press differed from Clinton's home town press which reported "the foot ball team of the Sentinel high school defeated the foot ball team of this place last Saturday by a score of 28-0." Whether it was 26 or 28-0, disappointment within this antiquated window of gridiron time can still be felt by Clinton fans well over a century later. With a slightly improved defense and no offense, Clinton was left standing in a dust blown wheat field with wonder of when and how they might win at this new game played on its plains.

Sentinel's home town press immediately recognized the boys from Clinton as being "quick," but, it seems the Sentinel eleven were somewhat quicker in 1910. With no doubt quickness can and will get you around the right or left end for a touchdown, that is just what happened when George Cobean scored the first ever touchdown against Clinton on an end run. John D. Terry made kick for a 7-0 Sentinel lead. Unfortunately for Clinton, this first seven points was all that was needed as the gridiron pioneers could not cross goal on a brisk Saturday afternoon down in Sentinel. A final score of 33 to 0 is not a good one to report, but, for those who follow Clinton football, it is known things turn out much better at various points of time in a future filled with great players and great teams.

The Sentinel game was considered interesting and with "many points worthy of commendation." Despite victory, the crowd was small and the Sentinel boys were left indebted near fifteen dollars, hence, the value of an enthusiastic booster club should never be taken for granted. Ironically, Clinton's focus on business growth first and football second may have actually paid off in the "long run" as its gridiron tradition continues to grow while many others in southwest Oklahoma, such as Sentinel, ceased to exist quite some time ago.

Suffering from a shutout loss and with little time for the boys from Clinton to improve, Sentinel returned the favor of game as they traveled to Clinton two weeks later to participate in a contest hosted by the Clinton eleven. This first home game itself was played under difficult conditions. The Clinton gridiron was hastily constructed in a wheat stubbled field freshly raked over within just a few hours before kick-off. The dry and sandy soil was near two inches deep. To grasp a true scope of the environment, readers can visualize a field running north and south with a strong north wind blasting mini sand drifts around the pointed and dry wheat stubble upon the red dirt western Oklahoma plains. With football officially kicking off in Clinton at 2 p.m. on October 29, 1910, both Sentinel and Clinton fumbled a few times as neither team scored in the first quarter of play. The Clinton defense had at least displayed some improvement within the two week span between these inaugural and antiquated contests.

In the second quarter, Sentinel took command by scoring touchdowns on a line buck and a criss-cross fake run. Bystanders, evidently from Sentinel, declared the game "remarkable" and the final score ended with another shutout of Clinton's eleven by a reported score of 26-0. With a criss cross check of facts, the 26-0 score revealed by the Sentinel press differed from Clinton's home town press which reported "the foot ball team of the Sentinel high school defeated the foot ball team of this place last Saturday by a score of 28-0." Whether it was 26 or 28-0, disappointment within this antiquated window of gridiron time can still be felt by Clinton fans well over a century later. With a slightly improved defense and no offense, Clinton was left standing in a dust blown wheat field with wonder of when and how they might win at this new game played on its plains.

J.D. Simpson Clothiers

J.D. Simpson Clothiers Football in Clinton was certainly not front page news in 1910 or even within the early parts of the previous century. The only other reference, at the time, to Clinton and its start up football program was discovered in a "school news" column published by the local press. "Foot ball season over. The boys have laid up their energy for this season. It is give up by all that John Stocks is the star player. Next season our boys will take everything in sight." The only other gridiron related item, discovered at the time, was an advertisement featuring football action in its background as J.D. Simpson marketed "vigor, spirit and snap" in his clothes for young men. This leaving a premonition that pioneering Clinton foot ball star John Stocks himself dropped by the Simpson store located in the Texas Building on West Frisco Avenue. Stocks would have looked real nice in a new brown, plaid or striped Ederheimer-Stein three piece with his choice of either two or three buttons on the jacket with additional options of medium or long roll lapels.

Was the season of 1910 just a two game home and home series against Sentinel? Could have been. The complete first season for the University of Oklahoma in 1895 consisted of just ... one game. The following year in 1896, the state university's season was extended to include a grand total of ... two games. The birth of football in Oklahoma and its growth into popularity as it spread west was a slow and tedious task. Whether it was a township team, high school team or collegiate eleven, the raw and basic beginnings of gridiron gain involved the recruitment of nearby farm boys who had to learn the game from scratch and move forward with minimal game experience from year to year. If they were lucky, some settler from the east and north may have migrated south and west with some form of game day knowledge and experience that sped up the process a tad bit.

Turns out the 1910 season was a tad bit more than two games. Exciting news from county press indicates Clinton would win at least one game in their long forgotten inaugural season. On November 11, 1910, Arapaho's eleven would come to town for a tussle on Clinton's high school grounds. Clinton's indigenous gridiron warriors would claim a 31-0 victory over their neighbor to the north. Over a century span of fans, coaches and players can thank Greg Adams (mid 1980's Red Tornado LB) for his archaeological discovery leading living enthusiasts towards an authentic introduction to some of Clinton's very first football ancestors who prowled the plains in search of a first victory. For all who happened to miss the game against Arapaho, it was a foundational cornerstone of victorious tradition for Clinton's community and school to celebrate.

With John Stocks noted as the "star" player in Clinton's kick-off season, he was missing in action (M.I.A.) for the offensive line-up against Arapaho. The only conclusion is Stocks either played one way on defense or was possibly a member of one of two teams that was formed at CHS in 1910. While being one of the last southwest Oklahoma communities to crank up a football program, it looks like Clinton, when they chose to start, did it big time with the formation of two football teams. Seems there was a sizeable transformation from minimal students in 1909 that enabled the fielding two football teams, including some seniors in 1910. Many Oklahoma schools and their districts were enlarged by consolidation in the year of 1910.

The first Clinton (offensive) eleven to capture a victory for their community and school would include some recognizable community family names that exist today. Avant at left end, MacAtee at left tackle, Taney at left guard, Griffin at center, Fisher at right guard, Burgreen at right tackle, Cain at right end, Burris at QB1, Shumate at left half, Crawford at right half and Koenig at full back. These Clinton football aboriginals captained by Ralph Avant and Byron Tansley played a "snappy" game in front of a less than large crowd made up of mostly school children. Arapaho showed up with a "poor showing" and the game was tailor made for an easy victory for Clinton. What seems to have been more like a pigskin tussle on the playground transformed into Clinton's first ever victory in their storied high school football history. The fans, coaches and players involved would become the first ever to experience Clinton's pride in winning relative to a football contest. A winning pride that continues to exist today and is expected to exist into an infinite future.

It would be near one full year before Clinton would get a chance to avenge the two goose egg defeats to the Sentinel team. With that chance coming on October 21, 1911, the Clinton eleven "took the game of football" from the Sentinel boys with no score posted and no in depth coverage from Sentinel's local press. With the storyline quickly transcending from football to base ball prowess and with no details, the loss may have been a large one for Sentinel. With no score posted and with mention of an upcoming return game in Sentinel the following Saturday, subject matter of football against Clinton was drop kicked hot off the press which leads historically enthusiastic football fans to believe either the second game did not take place or Clinton won by another big score on Saturday, November 28, 1911. It was not unusual for local press to skip over bad news related to sports but it would have been a bit unusual for Clinton's local press to ignore the good news of a Clinton victory if indeed it did happen.

Was the season of 1910 just a two game home and home series against Sentinel? Could have been. The complete first season for the University of Oklahoma in 1895 consisted of just ... one game. The following year in 1896, the state university's season was extended to include a grand total of ... two games. The birth of football in Oklahoma and its growth into popularity as it spread west was a slow and tedious task. Whether it was a township team, high school team or collegiate eleven, the raw and basic beginnings of gridiron gain involved the recruitment of nearby farm boys who had to learn the game from scratch and move forward with minimal game experience from year to year. If they were lucky, some settler from the east and north may have migrated south and west with some form of game day knowledge and experience that sped up the process a tad bit.

Turns out the 1910 season was a tad bit more than two games. Exciting news from county press indicates Clinton would win at least one game in their long forgotten inaugural season. On November 11, 1910, Arapaho's eleven would come to town for a tussle on Clinton's high school grounds. Clinton's indigenous gridiron warriors would claim a 31-0 victory over their neighbor to the north. Over a century span of fans, coaches and players can thank Greg Adams (mid 1980's Red Tornado LB) for his archaeological discovery leading living enthusiasts towards an authentic introduction to some of Clinton's very first football ancestors who prowled the plains in search of a first victory. For all who happened to miss the game against Arapaho, it was a foundational cornerstone of victorious tradition for Clinton's community and school to celebrate.

With John Stocks noted as the "star" player in Clinton's kick-off season, he was missing in action (M.I.A.) for the offensive line-up against Arapaho. The only conclusion is Stocks either played one way on defense or was possibly a member of one of two teams that was formed at CHS in 1910. While being one of the last southwest Oklahoma communities to crank up a football program, it looks like Clinton, when they chose to start, did it big time with the formation of two football teams. Seems there was a sizeable transformation from minimal students in 1909 that enabled the fielding two football teams, including some seniors in 1910. Many Oklahoma schools and their districts were enlarged by consolidation in the year of 1910.

The first Clinton (offensive) eleven to capture a victory for their community and school would include some recognizable community family names that exist today. Avant at left end, MacAtee at left tackle, Taney at left guard, Griffin at center, Fisher at right guard, Burgreen at right tackle, Cain at right end, Burris at QB1, Shumate at left half, Crawford at right half and Koenig at full back. These Clinton football aboriginals captained by Ralph Avant and Byron Tansley played a "snappy" game in front of a less than large crowd made up of mostly school children. Arapaho showed up with a "poor showing" and the game was tailor made for an easy victory for Clinton. What seems to have been more like a pigskin tussle on the playground transformed into Clinton's first ever victory in their storied high school football history. The fans, coaches and players involved would become the first ever to experience Clinton's pride in winning relative to a football contest. A winning pride that continues to exist today and is expected to exist into an infinite future.

It would be near one full year before Clinton would get a chance to avenge the two goose egg defeats to the Sentinel team. With that chance coming on October 21, 1911, the Clinton eleven "took the game of football" from the Sentinel boys with no score posted and no in depth coverage from Sentinel's local press. With the storyline quickly transcending from football to base ball prowess and with no details, the loss may have been a large one for Sentinel. With no score posted and with mention of an upcoming return game in Sentinel the following Saturday, subject matter of football against Clinton was drop kicked hot off the press which leads historically enthusiastic football fans to believe either the second game did not take place or Clinton won by another big score on Saturday, November 28, 1911. It was not unusual for local press to skip over bad news related to sports but it would have been a bit unusual for Clinton's local press to ignore the good news of a Clinton victory if indeed it did happen.

John Stocks

John Stocks Maybe the 1911 Clinton eleven made good on the previous year's school news prediction of "taking everything in sight?" Maybe Clinton's very first known foot ball star, John Stocks, returned to wreck havoc revenge upon those farm boys from down south in Sentinel? Maybe the first win over Arapaho motivated players to work harder and practice longer?

Recognized as one of Clinton's first known footballers and a star player, John Stocks was born in the spring of 1892 in the small Kansas town of Douglas in Butler County. After playing the first "star" role known to mankind and relative to the history of Clinton football, Stocks eventually became a rural mail carrier for the fine folks living outside the township limits of Clinton. In the year of 1930, Stocks moved to Hamilton, Texas and served in a similar capacity with the United States Postal Service. The Stocks family name would continue to show up on Clinton's gridiron grass well into the 1950's.

John Stocks' passing in the fall of 1944 was a surprise and quite sudden. Funeral services were held on October 10, 1944, at 2 p.m. under the direction of Kern and Schneider Funeral Home. Ironically a same start time as trailblazer Stocks and his Clinton eleven teammates kicked off their home football genesis on that sand filled wheat stubble field some thirty-four years previous. Reverend Edwin W. Parker of the First Methodist Church officiated Stocks' service with a burial that followed in the Arapaho cemetery. Survivors at the time of Stocks' death included wife Francis Blanche Mainard Stocks, one daughter Jo Ann Stocks; two sisters Mrs. J.W. Owen of Clinton and Mrs. Carl Goss of Las Vegas, Nevada; and two brothers Frank Stocks of Arapaho and Art Stocks of Foss. Some of Stocks' family members have carried the torch of tradition for Clinton's football program within the first half of the twentieth century.

With a somewhat rough and tumble steep learning curved genesis, the vague but inceptive seeds of Clinton's football tradition were at least planted by Stocks, Koenig, Crawford, Shumate, Burris, Cain, Burgreen, Fisher, Griffin, Taney, MacAtee, Avant and few other unidentified gridiron ghosts from the previous century. With determination, hard work and inclination to continually regurgitate the taste of losing, Clinton's football legacy wrestled with moderate to conference championship success until its actual state championship supremacy was bourne four and one half decades later. Along with this futuristic state championed supremacy, distinctively fabricated with natural gridironed talent devoutly integrated within a persevering spirit in the Lord's year of 1965, "the" iconic face of a tradition rich Red Tornado football program was conceived on the oft wind swept plains of west Oklahoma.

Recognized as one of Clinton's first known footballers and a star player, John Stocks was born in the spring of 1892 in the small Kansas town of Douglas in Butler County. After playing the first "star" role known to mankind and relative to the history of Clinton football, Stocks eventually became a rural mail carrier for the fine folks living outside the township limits of Clinton. In the year of 1930, Stocks moved to Hamilton, Texas and served in a similar capacity with the United States Postal Service. The Stocks family name would continue to show up on Clinton's gridiron grass well into the 1950's.

John Stocks' passing in the fall of 1944 was a surprise and quite sudden. Funeral services were held on October 10, 1944, at 2 p.m. under the direction of Kern and Schneider Funeral Home. Ironically a same start time as trailblazer Stocks and his Clinton eleven teammates kicked off their home football genesis on that sand filled wheat stubble field some thirty-four years previous. Reverend Edwin W. Parker of the First Methodist Church officiated Stocks' service with a burial that followed in the Arapaho cemetery. Survivors at the time of Stocks' death included wife Francis Blanche Mainard Stocks, one daughter Jo Ann Stocks; two sisters Mrs. J.W. Owen of Clinton and Mrs. Carl Goss of Las Vegas, Nevada; and two brothers Frank Stocks of Arapaho and Art Stocks of Foss. Some of Stocks' family members have carried the torch of tradition for Clinton's football program within the first half of the twentieth century.

With a somewhat rough and tumble steep learning curved genesis, the vague but inceptive seeds of Clinton's football tradition were at least planted by Stocks, Koenig, Crawford, Shumate, Burris, Cain, Burgreen, Fisher, Griffin, Taney, MacAtee, Avant and few other unidentified gridiron ghosts from the previous century. With determination, hard work and inclination to continually regurgitate the taste of losing, Clinton's football legacy wrestled with moderate to conference championship success until its actual state championship supremacy was bourne four and one half decades later. Along with this futuristic state championed supremacy, distinctively fabricated with natural gridironed talent devoutly integrated within a persevering spirit in the Lord's year of 1965, "the" iconic face of a tradition rich Red Tornado football program was conceived on the oft wind swept plains of west Oklahoma.

Roy Bell became the iconic face of Clinton Football with his dominate high school performances. Bell was selected All-State and Oklahoma's "Offensive Player Of The Year" as the state's scoring leader with 32 touchdowns. Roy Bell rushed the Red Tornadoes to their second state championship in 1967 and also played a key role, along with his older brother Carlos, in Clinton's very first state championship won in 1965.

If there were ever a football genesis prophet of action to trailblaze a path toward a pride filled and successful future for Clinton and anyone else to follow, the high honor goes to a Custer County lad by the name of Lawrence Meacham. With no known documented ties to the early day Clinton football program, Meacham grew up on a farm very near Clinton with seven other husky brothers and three sisters who transcended into the sports, business and education arenas in big ways. The Clinton area farm boys were all sons of Mr. and Mrs. George Allison Meacham. The Meacham family, considered by this passionate of subject matter historian as the first family of western Oklahoma football, were pioneering Cheyenne and Arapaho country settlers residing near the rural Parkersburg area about eight wheat fields west of Clinton.

In 1899, the future site of what was to become the township of Clinton existed as a small settlement just east of what had already become Meacham farms to its west. The Meacham family moved to Cheyenne Arapaho country in Oklahoma Territory in 1897. With no railroads available at that time, they traveled overland from Smithfield, Texas, herding horses and cattle towards what would become their homestead just to the west of what would become the territorial township of Clinton.

Albert Nance

Albert Nance Some twenty years post establishment and in the Lord's year of 1919, Clinton fullback and class historian Albert Nance utilized his high school leveled research skills to chronicle a genesis narrative of Clinton's township. Nance shared "early in the year of 1903, a party of men conceived the idea of building a town at the junction of the Choctaw and Frisco Railroads. In order to do this a hundred sixty acre tract of land would have to be obtained from the Indians to form a townsite. The Washita Townsite Company was created to buy land from the Indians. Forty acres were eventually purchased from each of the following land owners, Darwin Hayes, Shoeboy, Red Ploom and Nowahy."

More in-depth historical research reveals Nowahy had unintentionally sold land to the township of Arapaho who had implemented a reverse play action scheme of measures to stop the creation of a new nearby town. Lawyers investigated the sale of Nowahy's land and found there was no initial or official government "designation" for the sale to Arapaho making it null and void. Nowahy, who thought she had sold the land to the Washita Townsite Company, was then able to sell the remaining forty acres that paved the way for Clinton's official birthing date of June 6, 1903.

More modernly known as the "Hub City" of western Oklahoma, Clinton's turn of the century emphasis on business, agriculture and railroad growth quickly earned a well deserved reputation as "The Empress of the Southwest" by 1909. Relative to football, a solid foundation of community support had been established for the upcoming 1910 origination of what would become Oklahoma's most revered high school program. Some might consider Clinton's very first gridiron victory over Arapaho in 1910 as formidable payback for their personal foul and unnecessarily rough attempt at blocking the creation of Clinton as it existed then and as it exists today.

More in-depth historical research reveals Nowahy had unintentionally sold land to the township of Arapaho who had implemented a reverse play action scheme of measures to stop the creation of a new nearby town. Lawyers investigated the sale of Nowahy's land and found there was no initial or official government "designation" for the sale to Arapaho making it null and void. Nowahy, who thought she had sold the land to the Washita Townsite Company, was then able to sell the remaining forty acres that paved the way for Clinton's official birthing date of June 6, 1903.

More modernly known as the "Hub City" of western Oklahoma, Clinton's turn of the century emphasis on business, agriculture and railroad growth quickly earned a well deserved reputation as "The Empress of the Southwest" by 1909. Relative to football, a solid foundation of community support had been established for the upcoming 1910 origination of what would become Oklahoma's most revered high school program. Some might consider Clinton's very first gridiron victory over Arapaho in 1910 as formidable payback for their personal foul and unnecessarily rough attempt at blocking the creation of Clinton as it existed then and as it exists today.

Lawrence Meacham

Lawrence Meacham Back to football. No, the A is not for Altus, Arapaho or Anadarko. With no connections found to Clinton's gridiron legacy, Lawrence Meacham did learn to play football within a limited time span at Southwestern Normal School at nearby Weatherford in 1912. Southwestern Normal was established by an act of the Oklahoma Territorial Legislature in 1901. The Normal School was stamped for approval to provide two years of training and four years of preparatory work for students who were not age qualified for college admission.

This fascinating young man named Meacham, with minimal football experience offset with good size and natural speed and talent, was appointed to West Point Academy (the A is for Army) by Oklahoma Congressman Claude Weaver in January of 1913. The appointment by Congressman Weaver was not necessarily made for his gridiron talent, but, more for the young man's intellect and the admirable quality of character and integrity found within the Meacham family. After passing examination, Lawrence left the dust filled plains of the west arriving at West Point in the east on a cold and dreary February New York day in the Lord's year of 1913.

Despite limited gridiron experience, the young Meacham was good enough to be thrust into the starting line-up at a guard position for the 1913 Army eleven. The Cadets from West Point Academy compiled an 8-1 overall season record shutting out five of their nine opponents. The young farm raised Meacham seemed to enter an alien time warped tunnel in a west Oklahoma wheat field while passing through a magnificent plane of space and time with an exit into the threshold of West Point, New York. This within the blink of an unbelieving football loving eye.

Sharing Meacham "broke into football" his very first year at West Point is quite an understatement. He not only "broke in," he would soon be selected to Walter Camp's All-American team for his sophomore collegiate football efforts in the season of 1914. Camp, best known as "The Father of American Football," rewarded West Point's newcomer Meacham with third team honors for these extraordinary efforts on the gridiron. The nineteen year old 170 pound left guard skyrocketed from a limited learning process at Southwestern Normal to being considered one of Army's best lineman in 1913-1914. Meacham, as a rookie cadet, was noted as playing in every important game of the season while only missing a magnificent win over Navy due to injury.

With the traditional Army-Navy game approaching, the young west Oklahoma farm boy was considered a stellar performer on the underdog Army team. Pre-game fake news scouting reports reported Navy's two veteran guards to "clearly excel Meacham and Jones of Army." Although a disappointed Meacham had to watch from the sidelines, his reserve Huston and starting teammate Jones held their own as Army defeated Navy 22-9. The 1913 game was held at the infamous Polo Grounds in New York before a crowd of over 42,000 football and military enthusiasts. It was the nineteenth contest held between Army and Navy to date. Notable and historical figures in the crowd that particular day included newly elected United States President Woodrow Wilson as well as "America's greatest inventor" Thomas A. Edison.

Dealing with and defeating the freshman disappointment, Lawrence Meacham went on to become an anchor of the line for a very successful Army team from 1913 to 1916. While at West Point, Meacham and his cadet teammates split games with the mighty Notre Dame Fighting Irish. After losing a first go-around against All-American Knute Rockne and the Irish in 1913, Army won in 1914 by a score of 20-7 and also in Meacham's career concluding year as the eleven from West Point soundly defeated the Fighting Irish 30-10 in 1916.

This fascinating young man named Meacham, with minimal football experience offset with good size and natural speed and talent, was appointed to West Point Academy (the A is for Army) by Oklahoma Congressman Claude Weaver in January of 1913. The appointment by Congressman Weaver was not necessarily made for his gridiron talent, but, more for the young man's intellect and the admirable quality of character and integrity found within the Meacham family. After passing examination, Lawrence left the dust filled plains of the west arriving at West Point in the east on a cold and dreary February New York day in the Lord's year of 1913.

Despite limited gridiron experience, the young Meacham was good enough to be thrust into the starting line-up at a guard position for the 1913 Army eleven. The Cadets from West Point Academy compiled an 8-1 overall season record shutting out five of their nine opponents. The young farm raised Meacham seemed to enter an alien time warped tunnel in a west Oklahoma wheat field while passing through a magnificent plane of space and time with an exit into the threshold of West Point, New York. This within the blink of an unbelieving football loving eye.

Sharing Meacham "broke into football" his very first year at West Point is quite an understatement. He not only "broke in," he would soon be selected to Walter Camp's All-American team for his sophomore collegiate football efforts in the season of 1914. Camp, best known as "The Father of American Football," rewarded West Point's newcomer Meacham with third team honors for these extraordinary efforts on the gridiron. The nineteen year old 170 pound left guard skyrocketed from a limited learning process at Southwestern Normal to being considered one of Army's best lineman in 1913-1914. Meacham, as a rookie cadet, was noted as playing in every important game of the season while only missing a magnificent win over Navy due to injury.

With the traditional Army-Navy game approaching, the young west Oklahoma farm boy was considered a stellar performer on the underdog Army team. Pre-game fake news scouting reports reported Navy's two veteran guards to "clearly excel Meacham and Jones of Army." Although a disappointed Meacham had to watch from the sidelines, his reserve Huston and starting teammate Jones held their own as Army defeated Navy 22-9. The 1913 game was held at the infamous Polo Grounds in New York before a crowd of over 42,000 football and military enthusiasts. It was the nineteenth contest held between Army and Navy to date. Notable and historical figures in the crowd that particular day included newly elected United States President Woodrow Wilson as well as "America's greatest inventor" Thomas A. Edison.

Dealing with and defeating the freshman disappointment, Lawrence Meacham went on to become an anchor of the line for a very successful Army team from 1913 to 1916. While at West Point, Meacham and his cadet teammates split games with the mighty Notre Dame Fighting Irish. After losing a first go-around against All-American Knute Rockne and the Irish in 1913, Army won in 1914 by a score of 20-7 and also in Meacham's career concluding year as the eleven from West Point soundly defeated the Fighting Irish 30-10 in 1916.

Benjamin Hoge

Benjamin Hoge Following such a superb season, Lawrence Meacham's superman cadet teammate and captain of the 1913 Army team, Benjamin F. Hoge, shared four points of gridiron wisdom that could and should be absorbed for motivational use by any player or coach who chooses to step a foot on a field. Captain Hoge was the first to implement spring and summer practices at West Point with intent on perfecting the fundamentals of punting, place-kicking, passing and maintaining good physical shape for the battles of the upcoming fall football season.

Addressing the Corps of Cadets on New Year's Day, 1914, Hoge's four points of post season wisdom shared with Meacham and other cadets called upon to carry the torch of success for the Army football team included:

(1) "Every man who intends to play the game should turn out for Spring and Summer practice. Individual excellence counts more than ever before, and this is a great chance to practice drop kicking, punting, place kicking, passing and receiving the ball, catching punts and running. If you weigh 150 pounds and have the right spirit, you can, by consistent, intelligent practice, become a good player. But to do it requires the denial of many 'spooning formations' and privilege rides. Also the ability to stick to it under all discouragements and never give up. Don't forget that you are in college (or high school) for only four years and have all the remainder of your life for other things."

(2) "We now have an excellent system in the Corps of keeping tab on each athlete's class work. By means of this system we lost no valuable material during the last year. This is an untold help to the coaches, as they cannot afford to develop men to be lost just when needed, or when it is too late to train men for their places. Let us keep up this system."

(3) "The spirit displayed by each cadet as an individual and each class as a whole unit could not have been better. It is absolutely impossible to win in athletics, and in football particularly, unless there is but one opinion and one spirit. There must never be cliques or factions pulling for one class or one individual. Each man has his work to do, and there is but one aim to it all, namely - win from Annapolis (Navy) and keep West Point (Army) on top."

(4) "We must guard against overconfidence. What happened to the Navy team last year (1913) by way of overconfidence should be an example to us never to be forgotten. Don't ever forget it. For a team to play its best game it must feel that there is only bare a chance of winning, and that the battle will be won only by all eleven men doing their work every minute of the contest. This is the spirit which every Army team should meet the Navy. A team in this frame of mind will play a fifty percent better game than it would ordinarily."

Interestingly upon arriving at West Point, Meacham unknowingly discovered two other principled teammates who would transcend into higher realms of leadership for both the U.S. Army and the United States of America. Omar and Ike were members of Army's football roster as Meacham stepped onto his very first spring practice field at West Point. Fellow cadet and teammate Omar Nelson Bradley would become a senior officer during World War II and eventually "the" General of the Army from 1949 to 1953. Bradley would also become the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who would oversee the U.S. military's policy-making in the Korean War.

As for teammate and cadet Ike, he would become the caretaker and carrier of the pre-game flag for Army's Honor Guard. The somewhat undisciplined cadet and football player would give up the game not long after Meacham arrived but did take pride in his new and highly regarded Honor Guard position. The red white and blue had come to mean something most special to Meacham's gridiron teammate and young Army Honor Guard constituent named Ike. "When we raised our right hands and repeated the official oath, there was no confusion. A feeling came over me that the expression 'The United States of America' would now and henceforth mean something different than it ever had before. From here on it would be the nation I would be serving, not myself. Suddenly the flag itself meant something," shared a most patriotic Ike who would later become known as United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Addressing the Corps of Cadets on New Year's Day, 1914, Hoge's four points of post season wisdom shared with Meacham and other cadets called upon to carry the torch of success for the Army football team included:

(1) "Every man who intends to play the game should turn out for Spring and Summer practice. Individual excellence counts more than ever before, and this is a great chance to practice drop kicking, punting, place kicking, passing and receiving the ball, catching punts and running. If you weigh 150 pounds and have the right spirit, you can, by consistent, intelligent practice, become a good player. But to do it requires the denial of many 'spooning formations' and privilege rides. Also the ability to stick to it under all discouragements and never give up. Don't forget that you are in college (or high school) for only four years and have all the remainder of your life for other things."

(2) "We now have an excellent system in the Corps of keeping tab on each athlete's class work. By means of this system we lost no valuable material during the last year. This is an untold help to the coaches, as they cannot afford to develop men to be lost just when needed, or when it is too late to train men for their places. Let us keep up this system."

(3) "The spirit displayed by each cadet as an individual and each class as a whole unit could not have been better. It is absolutely impossible to win in athletics, and in football particularly, unless there is but one opinion and one spirit. There must never be cliques or factions pulling for one class or one individual. Each man has his work to do, and there is but one aim to it all, namely - win from Annapolis (Navy) and keep West Point (Army) on top."

(4) "We must guard against overconfidence. What happened to the Navy team last year (1913) by way of overconfidence should be an example to us never to be forgotten. Don't ever forget it. For a team to play its best game it must feel that there is only bare a chance of winning, and that the battle will be won only by all eleven men doing their work every minute of the contest. This is the spirit which every Army team should meet the Navy. A team in this frame of mind will play a fifty percent better game than it would ordinarily."

Interestingly upon arriving at West Point, Meacham unknowingly discovered two other principled teammates who would transcend into higher realms of leadership for both the U.S. Army and the United States of America. Omar and Ike were members of Army's football roster as Meacham stepped onto his very first spring practice field at West Point. Fellow cadet and teammate Omar Nelson Bradley would become a senior officer during World War II and eventually "the" General of the Army from 1949 to 1953. Bradley would also become the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who would oversee the U.S. military's policy-making in the Korean War.

As for teammate and cadet Ike, he would become the caretaker and carrier of the pre-game flag for Army's Honor Guard. The somewhat undisciplined cadet and football player would give up the game not long after Meacham arrived but did take pride in his new and highly regarded Honor Guard position. The red white and blue had come to mean something most special to Meacham's gridiron teammate and young Army Honor Guard constituent named Ike. "When we raised our right hands and repeated the official oath, there was no confusion. A feeling came over me that the expression 'The United States of America' would now and henceforth mean something different than it ever had before. From here on it would be the nation I would be serving, not myself. Suddenly the flag itself meant something," shared a most patriotic Ike who would later become known as United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

1913 West Point cadet and offensive lineman Lawrence Meacham (2nd from left) grew up with seven brothers on a farm just west of Clinton, Oklahoma. As a starter in his first year, Meacham played in the very first Army vs. Notre Dame contest and against the legendary Knute Rockne.

Although Meacham's collegiate football career at West Point did not garner any first team All-American honors as may have been expected, his 1915 Army team captain, Lieutenant A.M. Weyand, persisted that the 170 pound farm boy guard from west Oklahoma "had never been outplayed throughout his four seasons on the team." This statement of fact coming from a man of high honor and integrity who played in the trenches along side Meacham on almost every play in every game. Considering Walter Camp's inability to see every player's play in every game, the honorable statement from Army's football Captain Weyand would seem to carry more considerable weight for Meacham and his invaluable contributions to the Army squads of 1913-1916.

The U.S. Army did allow Lawrence Meacham a return home visit to his Custer County roots before his entering active service in the military. The very first West Point cadet from Custer County was acknowledged by state press as Lieutenant Meacham, a star of West Point football team, and brother of Representative E.J. Meacham and Custer County Superintendent of Schools George Meacham Jr. during this return to home visit. This homecoming visitation took place shortly after Meacham's official West Point graduation in the spring of 1917.

Ironically before Colonel Lawrence Meacham, the boy from Oklahoma, had played football for Army, the Army had played "foot-ball" in Oklahoma some eighteen years earlier. Two years before the 20th Infantry arrived at Caddo Springs (near El Reno, Oklahoma) in 1885, Reverend H. Miller of the Presbyterian Church in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, had shipped a Christmas box to the Cheyenne Boarding School. When opened, the boys of the school immediately grabbed the "foot-ball" which provided excellent amusement and exercise. Under the tutelage of Professor Potter, the Cheyenne boys were drilled into a somewhat competitive and organized "foot-ball" team. Within two years, Stacy Riggs, Robert Sandhill and their fellow teammates of the Cheyenne school were publicly challenging the young men of the Darlington Agency, Fort Reno soldiers and the boys of the Arapaho school to play a game of "foot-ball."

Upon arrival of United States Army, 20th Infantry, Companies C and D to Caddo Springs (now known as Concho, Oklahoma) in May of 1885, the enthusiastic Cheyenne boys were quick to challenge the travelling soldiers to a game of "foot-ball." After pitching their tents for camp, the travel weary troops enthusiastically accepted the challenge of participating in what could be Oklahoma's first "foot ball" game with official Caddo Springs kick off called at 6:30 p.m. The soldiers had spent the past few months engaged in the removal of intruders and trespassers from west Oklahoma's public lands. After marching 188 miles in the process of returning to their station at Fort Reno in Indian Territory, the soldiers found themselves in the middle of some "foot-ball" action against the Cheyenne school boys.

After winning the toss, a selected team of soldiers went on the offensive but soon found themselves outplayed by the firm and rapid movements of the well trained school boys. After winning two games before sundown, the confidence of the Cheyenne school boys was encouraged by the presence of their superintendent, Dr. Whiting. With such confidence and courage, the "foot-ball" club accepted a challenge to play the soldiers again on the forenoon of the fourth of July at Fort Reno in 1885. With three of their teammates moving, ironically but unrelated, to the Lawrence School, the Cheyenne boys were unable to meet the challenge at Fort Reno on the fourth. They claimed, however, that their opponents "should be thankful that such was the case, as it undoubtedly saved them from sustaining another defeat."

Although Meacham's collegiate football career at West Point did not garner any first team All-American honors as may have been expected, his 1915 Army team captain, Lieutenant A.M. Weyand, persisted that the 170 pound farm boy guard from west Oklahoma "had never been outplayed throughout his four seasons on the team." This statement of fact coming from a man of high honor and integrity who played in the trenches along side Meacham on almost every play in every game. Considering Walter Camp's inability to see every player's play in every game, the honorable statement from Army's football Captain Weyand would seem to carry more considerable weight for Meacham and his invaluable contributions to the Army squads of 1913-1916.

The U.S. Army did allow Lawrence Meacham a return home visit to his Custer County roots before his entering active service in the military. The very first West Point cadet from Custer County was acknowledged by state press as Lieutenant Meacham, a star of West Point football team, and brother of Representative E.J. Meacham and Custer County Superintendent of Schools George Meacham Jr. during this return to home visit. This homecoming visitation took place shortly after Meacham's official West Point graduation in the spring of 1917.

Ironically before Colonel Lawrence Meacham, the boy from Oklahoma, had played football for Army, the Army had played "foot-ball" in Oklahoma some eighteen years earlier. Two years before the 20th Infantry arrived at Caddo Springs (near El Reno, Oklahoma) in 1885, Reverend H. Miller of the Presbyterian Church in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, had shipped a Christmas box to the Cheyenne Boarding School. When opened, the boys of the school immediately grabbed the "foot-ball" which provided excellent amusement and exercise. Under the tutelage of Professor Potter, the Cheyenne boys were drilled into a somewhat competitive and organized "foot-ball" team. Within two years, Stacy Riggs, Robert Sandhill and their fellow teammates of the Cheyenne school were publicly challenging the young men of the Darlington Agency, Fort Reno soldiers and the boys of the Arapaho school to play a game of "foot-ball."

Upon arrival of United States Army, 20th Infantry, Companies C and D to Caddo Springs (now known as Concho, Oklahoma) in May of 1885, the enthusiastic Cheyenne boys were quick to challenge the travelling soldiers to a game of "foot-ball." After pitching their tents for camp, the travel weary troops enthusiastically accepted the challenge of participating in what could be Oklahoma's first "foot ball" game with official Caddo Springs kick off called at 6:30 p.m. The soldiers had spent the past few months engaged in the removal of intruders and trespassers from west Oklahoma's public lands. After marching 188 miles in the process of returning to their station at Fort Reno in Indian Territory, the soldiers found themselves in the middle of some "foot-ball" action against the Cheyenne school boys.

After winning the toss, a selected team of soldiers went on the offensive but soon found themselves outplayed by the firm and rapid movements of the well trained school boys. After winning two games before sundown, the confidence of the Cheyenne school boys was encouraged by the presence of their superintendent, Dr. Whiting. With such confidence and courage, the "foot-ball" club accepted a challenge to play the soldiers again on the forenoon of the fourth of July at Fort Reno in 1885. With three of their teammates moving, ironically but unrelated, to the Lawrence School, the Cheyenne boys were unable to meet the challenge at Fort Reno on the fourth. They claimed, however, that their opponents "should be thankful that such was the case, as it undoubtedly saved them from sustaining another defeat."

Edgar Meacham

Edgar Meacham Lawrence Meacham's brother Edgar, concurrently, was a popular football player and scholar at the University of Oklahoma. Simultaneously with Clinton, Oklahoma University and its parogonic coach, Benny Owen, had been laboring their own way through football birthing pains and toward a bourne supremacy on the plains. Edgar also played guard and was considered, at the time, to be one of the best linemen the Sooners ever had in his position. Same as Clinton, the Sooners had worked through "a good many sad defeats," but, Edgar Meacham was acknowledged for his great effort, attitude and sportsmanship "no matter what the outcome of any game."

After attending Southwestern Normal and playing football in Weatherford, Meacham served as superintendent of Lookeba (Oklahoma) schools in 1910-1911 before arriving on campus at the state's university (OU) in the fall of 1911. With academics always a priority, his love for football would keep him on the field for another fifteen years multitasking his many talented skills. Meacham arrived in time for OU's first undefeated season under the guiding light of the infamous Bennie Owen in 1911. Edgar was the only first-year man on the squad to letter in football. Much like today's hurry-up offense, Meacham graduated in three years lettering in both football and track. He would serve as assistant coach to Bennie Owen for another ten years after concluding his football playing days in 1913.

The Sooner football star was selected by popular vote of the student body as the winner of the Letzeiser Medal in the spring of 1914. The annual award was sponsored by Letzeiser Jewelry Company of Oklahoma City and given to the best "all-around" student at the University of Oklahoma. Meacham was selected based upon 50% for scholarship, 20% for student activities, 20% for athletics and 10% for literary work.

E.J. Meacham, a younger football playing brother of Lawrence and Edgar, entered law school at the University of Oklahoma in the fall of 1915. After playing football at Southwestern Normal for the previous three years, E.J. would also join the Sooners gridiron gang as a second Meacham brother to play for Bennie Owen and pursue higher education at the state's university in Norman.

With no evidence that either of the three original Meacham brothers played for Clinton before representing West Point Academy and Oklahoma University in Norman, a few of their siblings and descendants would in fact contribute, in a large way, to the early and mid twentieth century construction of Clinton's Red Tornado football legacy. As for Colonel Lawrence Meacham, he fought for the freedom and rights of anyone and everyone to believe whether or not they believe he and his brother Edgar should be considered the Godfathers of Clinton football.

After attending Southwestern Normal and playing football in Weatherford, Meacham served as superintendent of Lookeba (Oklahoma) schools in 1910-1911 before arriving on campus at the state's university (OU) in the fall of 1911. With academics always a priority, his love for football would keep him on the field for another fifteen years multitasking his many talented skills. Meacham arrived in time for OU's first undefeated season under the guiding light of the infamous Bennie Owen in 1911. Edgar was the only first-year man on the squad to letter in football. Much like today's hurry-up offense, Meacham graduated in three years lettering in both football and track. He would serve as assistant coach to Bennie Owen for another ten years after concluding his football playing days in 1913.

The Sooner football star was selected by popular vote of the student body as the winner of the Letzeiser Medal in the spring of 1914. The annual award was sponsored by Letzeiser Jewelry Company of Oklahoma City and given to the best "all-around" student at the University of Oklahoma. Meacham was selected based upon 50% for scholarship, 20% for student activities, 20% for athletics and 10% for literary work.

E.J. Meacham, a younger football playing brother of Lawrence and Edgar, entered law school at the University of Oklahoma in the fall of 1915. After playing football at Southwestern Normal for the previous three years, E.J. would also join the Sooners gridiron gang as a second Meacham brother to play for Bennie Owen and pursue higher education at the state's university in Norman.

With no evidence that either of the three original Meacham brothers played for Clinton before representing West Point Academy and Oklahoma University in Norman, a few of their siblings and descendants would in fact contribute, in a large way, to the early and mid twentieth century construction of Clinton's Red Tornado football legacy. As for Colonel Lawrence Meacham, he fought for the freedom and rights of anyone and everyone to believe whether or not they believe he and his brother Edgar should be considered the Godfathers of Clinton football.

Rivers M. Randle

Rivers M. Randle As the three older Meacham brothers excelled at Army and OU, the Clinton football program was battling its way past some dark days and towards a brighter future that would eventually unfold in the early 1920's. While high school teams from around the state were posting scores and highlights of 1915 football action, Clinton High School was sidelined for the entire season due to a severe player injury from the previous 1914 season. Clinton principal and athletic coach Rivers M. Randle shared with state press, "the player injury is responsible for the absence of football for our local eleven." Coach Randle's somewhat vague statement would leave many to believe that Clinton had been playing football and a Clinton player had suffered great injury causing the suspension of the high school's football program. Examination of facts exhumed from 1914 divulges that Clinton probably did not play a down that particular year, but, they did host an exciting game between Cordell and Elk City. For this to happen, gridiron theologians could conclude that Clinton was in fact a football savvy town and they evidently had a field attractive enough to attract the attention of surrounding towns willing to travel to Clinton and square off their high school elevens in front of what was reportedly the largest crowd, at the time, to see a football game in the state of Oklahoma.

Tom Russell

Tom Russell Hard line plunging research reveals the hyped up large crowd was to become witness to a most severe football injury that happened to an Elk City player and tragically occurred in a game against Cordell which was hosted by the community of Clinton in 1914. Tom Russell, a 170 pound fullback for Elk City joined their 1914 squad after another player (Hunter) suffered a sever knee injury. Russell's injury in the game against Cordell reportedly paralyzed him from the chest down.

Local Elk City coverage shared a descriptive of immediate consequence for this atrocious injury that happened in the fall of 1914. "The unfortunate incident which occurred at Clinton not only barred foot-ball from our school, and dropped a blanket of sorrow over all Southwestern Oklahoma, but also perhaps permanently disabled one of the most naturally talented players who ever donned the moleskins."

Before the gathered crowd which was reported to be the largest audience to ever witness a high school football contest in western Oklahoma, if not the entire state, Cordell defeated Elk City 42-13 at Clinton on November 20, 1914. The weather was unusually warm for football players but great for the large crowd of spectators and enthusiasts congregated on the sidelines while almost encroaching the field of play. All was considered good until the paralyzing injury to Tom Russell happened with just a few minutes to play. Upon head on contact with fierce effort to tackle a Cordell halfback, Tom Russell was not expected to live through such horrendous injury sustained. With Cordell well in control of the game, Russell broke through the line of interference and rammed head first into one of the Cordell players. The impact visually made a depression on the brain and instantly paralyzed Russell from the chest down. Russell was transported to Clinton Hospital and later removed to his home in Elk City with improved chances of "probable" recovery.

What brought the two teams together for a clash in Clinton was a controversial game played two weeks previous in Elk City. The home team refused to play unless they were granted permission to use their own personally selected school teacher referee instead of the standard "courtesy" referee provided by the visiting team from Cordell. After an hour of battle against Elk City, the referee and near one hundred home team fans, Cordell literally had to "escape" with a tie game and most of the skin on their hide.

After Cordell gained a 7-0 lead, the home grown official began to operate against fairness to the game and towards home team favor. Allowing infractions against the home team to go uncalled was not as obvious but prevailed to the wishes of a rambunctious home crowd. Sometimes giving Elk City five downs was most obvious and quite unfair to the game and all players involved.

Despite the less obvious and the obvious, Cordell's well trained eleven held their own, forged a lead, and was driving to extend that lead when outraged fans encroached the field. In a rush, they surrounded the Cordell team while waving their fists in the air with a few blows landing here and there during this uncalled for melee of madness. After the field was cleared of fanatical fans and, get this, one Cordell player was ejected, the visiting team from Cordell drove the ball close enough into Elk City territory to attempt and miss what would have been the game winning field goal.

This particular game was a true reflection of the old "mob" style of football games from nineteenth century Europe. Home crowd intimidation ruled both the game and their personally selected referee. Elk City, utilizing the fear factor created within a weird scienced and archaic gridiron gangster environment, scored their only touchdown in the fourth quarter. The kick to follow actually fell a couple of feet short, but, while looking around at the angry mob of home team fans, the fearful referee held up his hands with a clear signal of good ending the game in a 7-7 tie with hopes of squelching any potential riots from the unruly home team fans.

The community of Clinton became a safe haven mediator site following the fiasco in Elk City. Both teams looked forward to squaring off on a fair and square gridiron. Special arrangements were made with the Frisco to hold the evening south bound train to give Cordell fans an opportunity to see the entire tie deciding game. On November 20, 1914, fans from Elk City, Cordell and Clinton made up what was mentioned as the largest crowd to see a game in western Oklahoma. A game played to conquer the unheard of and dishonorable use of home grown officiating in the previous football game. Who better to bring fairness and experience to the game than Oklahoma University standout and now coach Edgar Meacham? Under Meacham's rule as referee, it was either teams opportunity to win with honor and dignity. Cordell did just that with their 42-13 victory. A sweet taste of victory that was embittered for all with Tom Russell's paralyzing injury as he lay motionless on a long forgotten football field of vengeance and sorrow in Clinton, Oklahoma.

While Elk City's Russell was not expected to live and survived, a Hobart player, who was expected live, died in the following fall of 1915. Seventeen year old Clark Mansell did not survive a broken shoulder blade and severe spinal injury that paralyzed him from the waist down in Hobart's 68-0 win over Snyder on October 22. Mansell, son of a Hobart Judge, died in an Oklahoma City hospital on October 28, 1915, one week after the game took place in Hobart. Local, state and national press covered the tragic news. Mansell's injury was recognized as the "first death from a football injury in the state of Oklahoma this year." A bit eerie as the statement reflects an open end to the high probability of others. Luckily there were no more deaths due to football in Oklahoma in 1915. Mansell would be one of fifteen college and high school players nationwide to lose their life while participating in the game of football in 1915. Ages would range from eleven, fourteen and fifteen years old on up to twenty years old.

Some southwest Oklahoma schools suspended their football programs after Mansell's death. Tom Russell's paralyzing injury in 1914 and Mansell's death in 1915 were the determining factors as to why Clinton's eleven could not be found on the Oklahoma high school football map in 1916 as well. Some schools would return to the gridiron earlier than others. Additional hard line plunging research leads fans, coaches and players toward a sound of silence theoretical thought that it would be the post World War I fall of 1919 before Clinton would officially play another down of football on the fear filled, disheartened and quiet plains of western Oklahoma.

Local Elk City coverage shared a descriptive of immediate consequence for this atrocious injury that happened in the fall of 1914. "The unfortunate incident which occurred at Clinton not only barred foot-ball from our school, and dropped a blanket of sorrow over all Southwestern Oklahoma, but also perhaps permanently disabled one of the most naturally talented players who ever donned the moleskins."

Before the gathered crowd which was reported to be the largest audience to ever witness a high school football contest in western Oklahoma, if not the entire state, Cordell defeated Elk City 42-13 at Clinton on November 20, 1914. The weather was unusually warm for football players but great for the large crowd of spectators and enthusiasts congregated on the sidelines while almost encroaching the field of play. All was considered good until the paralyzing injury to Tom Russell happened with just a few minutes to play. Upon head on contact with fierce effort to tackle a Cordell halfback, Tom Russell was not expected to live through such horrendous injury sustained. With Cordell well in control of the game, Russell broke through the line of interference and rammed head first into one of the Cordell players. The impact visually made a depression on the brain and instantly paralyzed Russell from the chest down. Russell was transported to Clinton Hospital and later removed to his home in Elk City with improved chances of "probable" recovery.

What brought the two teams together for a clash in Clinton was a controversial game played two weeks previous in Elk City. The home team refused to play unless they were granted permission to use their own personally selected school teacher referee instead of the standard "courtesy" referee provided by the visiting team from Cordell. After an hour of battle against Elk City, the referee and near one hundred home team fans, Cordell literally had to "escape" with a tie game and most of the skin on their hide.

After Cordell gained a 7-0 lead, the home grown official began to operate against fairness to the game and towards home team favor. Allowing infractions against the home team to go uncalled was not as obvious but prevailed to the wishes of a rambunctious home crowd. Sometimes giving Elk City five downs was most obvious and quite unfair to the game and all players involved.

Despite the less obvious and the obvious, Cordell's well trained eleven held their own, forged a lead, and was driving to extend that lead when outraged fans encroached the field. In a rush, they surrounded the Cordell team while waving their fists in the air with a few blows landing here and there during this uncalled for melee of madness. After the field was cleared of fanatical fans and, get this, one Cordell player was ejected, the visiting team from Cordell drove the ball close enough into Elk City territory to attempt and miss what would have been the game winning field goal.

This particular game was a true reflection of the old "mob" style of football games from nineteenth century Europe. Home crowd intimidation ruled both the game and their personally selected referee. Elk City, utilizing the fear factor created within a weird scienced and archaic gridiron gangster environment, scored their only touchdown in the fourth quarter. The kick to follow actually fell a couple of feet short, but, while looking around at the angry mob of home team fans, the fearful referee held up his hands with a clear signal of good ending the game in a 7-7 tie with hopes of squelching any potential riots from the unruly home team fans.

The community of Clinton became a safe haven mediator site following the fiasco in Elk City. Both teams looked forward to squaring off on a fair and square gridiron. Special arrangements were made with the Frisco to hold the evening south bound train to give Cordell fans an opportunity to see the entire tie deciding game. On November 20, 1914, fans from Elk City, Cordell and Clinton made up what was mentioned as the largest crowd to see a game in western Oklahoma. A game played to conquer the unheard of and dishonorable use of home grown officiating in the previous football game. Who better to bring fairness and experience to the game than Oklahoma University standout and now coach Edgar Meacham? Under Meacham's rule as referee, it was either teams opportunity to win with honor and dignity. Cordell did just that with their 42-13 victory. A sweet taste of victory that was embittered for all with Tom Russell's paralyzing injury as he lay motionless on a long forgotten football field of vengeance and sorrow in Clinton, Oklahoma.

While Elk City's Russell was not expected to live and survived, a Hobart player, who was expected live, died in the following fall of 1915. Seventeen year old Clark Mansell did not survive a broken shoulder blade and severe spinal injury that paralyzed him from the waist down in Hobart's 68-0 win over Snyder on October 22. Mansell, son of a Hobart Judge, died in an Oklahoma City hospital on October 28, 1915, one week after the game took place in Hobart. Local, state and national press covered the tragic news. Mansell's injury was recognized as the "first death from a football injury in the state of Oklahoma this year." A bit eerie as the statement reflects an open end to the high probability of others. Luckily there were no more deaths due to football in Oklahoma in 1915. Mansell would be one of fifteen college and high school players nationwide to lose their life while participating in the game of football in 1915. Ages would range from eleven, fourteen and fifteen years old on up to twenty years old.

Some southwest Oklahoma schools suspended their football programs after Mansell's death. Tom Russell's paralyzing injury in 1914 and Mansell's death in 1915 were the determining factors as to why Clinton's eleven could not be found on the Oklahoma high school football map in 1916 as well. Some schools would return to the gridiron earlier than others. Additional hard line plunging research leads fans, coaches and players toward a sound of silence theoretical thought that it would be the post World War I fall of 1919 before Clinton would officially play another down of football on the fear filled, disheartened and quiet plains of western Oklahoma.

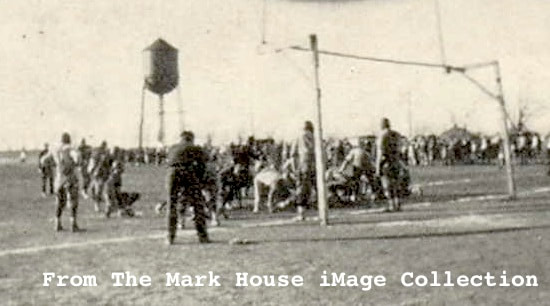

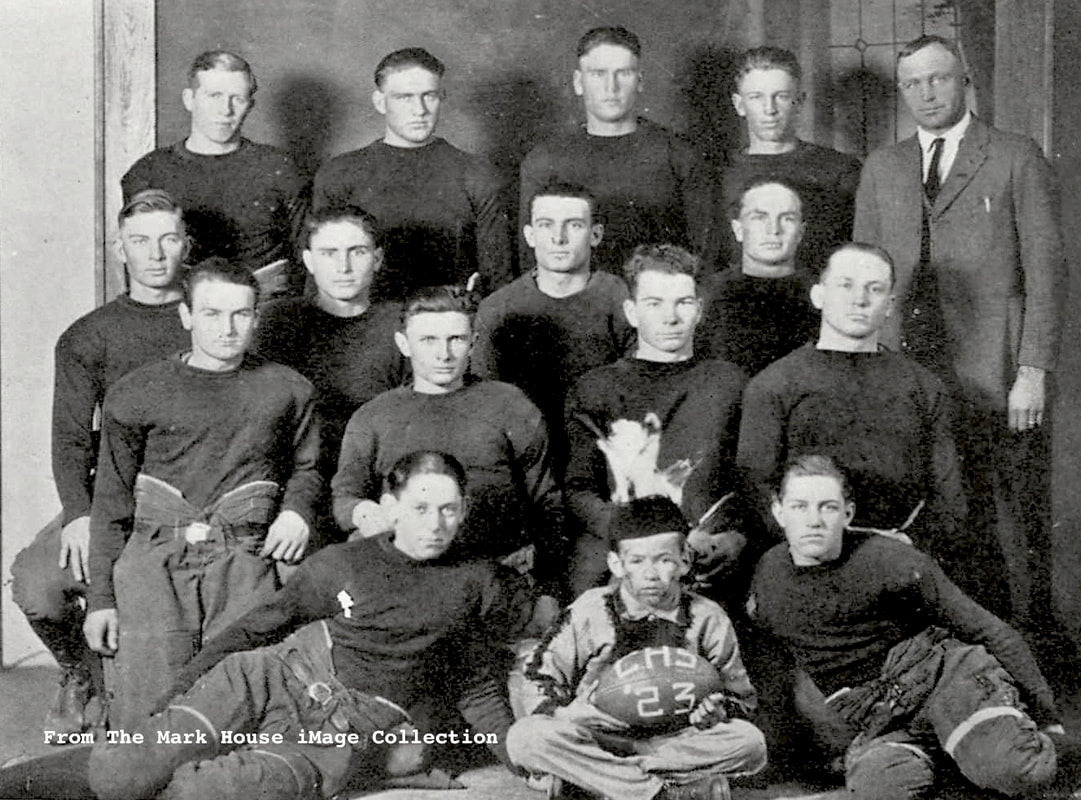

These gridiron greats of 1919 returned Clinton to Oklahoma's football map after a player injury (1914) and a player death (1915) combined with a delay of normalcy caused by World War I. Players representing the pioneer Clinton family names of Northrip, Armstrong, Donley, Hanshaw, Jones, Lamb, Vaughn, Nance, Lowrance, Peach, Meacham and Pemberton delivered a return season of a few victories, a few defeats and a tie.

Even in 1919, it was big news when Clinton ended up on the wrong side of defeat. One documentation of such defeat revealed the one and only (high school) loss Clinton suffered in 1919 carried some bragadocious Bull Dog verbage as the fresh but talented eleven from Clinton fought valiantly to a one point deficit. Even bigger news seems to be everyone had forgotten the tragedy of 1914 that suspended football action up to and through World War I. Within a span of nine years without internet access, John Stocks and his comrades who took on Sentinel in the fall of 1910 not only became old news fast, they were completely forgotten. The historic first win against Arapaho in 1910 and the gridiron vengeance against Sentinel in 1911 totally erased.

With a new administration and a new coach looking to construct post war success, evidently Clinton and its gridiron gang gazed forward without looking backwards and actually fielded a highly competitive team in 1919. New head coach Joyce (J.C.) Stearns had graduated from Snyder High School in 1915. Stearns' football formulated resume included a quick two years to higher education as he graduated from Kingfisher College in 1917. In the fall of 1915, Stearns quarterbacked the college to 67-0 loss against Bennie Owen's Sooners from Norman with Edgar Meacham on the OU staff as assistant coach. In the fall of 1916, Stearns quarterbacked the college from Kingfisher to a 97-0 loss at the hands of the mighty Sooners.

After graduating from the small college of Kingfisher in 1917, Stearns enlisted in the Navy where he served until January of 1919. He completed courses in Electrical and Submarine schools earning the highest 3.94 grade honors in his class. After serving Clinton's public school system as coach and principal, Stearns would move on to earn a doctorate in physics at the University of Chicago in Illinois and would, in due course, become heavily involved in the Manhattan Project that would eventually produce a means (atomic bomb) to the end of World War II. A post war Stearns would become an advocate for restricting the use of atomic energy relative to its mass destruction of mankind.

Even in 1919, it was big news when Clinton ended up on the wrong side of defeat. One documentation of such defeat revealed the one and only (high school) loss Clinton suffered in 1919 carried some bragadocious Bull Dog verbage as the fresh but talented eleven from Clinton fought valiantly to a one point deficit. Even bigger news seems to be everyone had forgotten the tragedy of 1914 that suspended football action up to and through World War I. Within a span of nine years without internet access, John Stocks and his comrades who took on Sentinel in the fall of 1910 not only became old news fast, they were completely forgotten. The historic first win against Arapaho in 1910 and the gridiron vengeance against Sentinel in 1911 totally erased.

With a new administration and a new coach looking to construct post war success, evidently Clinton and its gridiron gang gazed forward without looking backwards and actually fielded a highly competitive team in 1919. New head coach Joyce (J.C.) Stearns had graduated from Snyder High School in 1915. Stearns' football formulated resume included a quick two years to higher education as he graduated from Kingfisher College in 1917. In the fall of 1915, Stearns quarterbacked the college to 67-0 loss against Bennie Owen's Sooners from Norman with Edgar Meacham on the OU staff as assistant coach. In the fall of 1916, Stearns quarterbacked the college from Kingfisher to a 97-0 loss at the hands of the mighty Sooners.