One of baseball's greatest pitchers killed a man. Seems to be all that is remembered of Carl "Sub" Mays with case closed on his Hall Of Fame deservability. Well, while diggin' around in Mays' closed case file, I have come to believe it should be reopened, reaccessed and reconsidered for Hall Of Fame induction and recognition. As the underhand styled pitcher nicknamed "Sub" passed away in 1971, I can picture my fellow Oklahoman Jim Rockford (James Garner) preparing to head down to the LAPD and get his friend Sgt. Becker to open this case back up with valiant effort to seek a more honorable result.

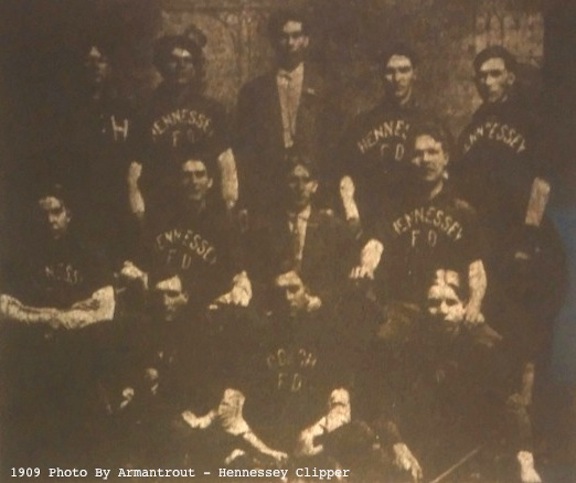

Where to start? I have discovered Carl and I have a few things in common. We were both seventeen year old pitchers when winning amateur level games within the same town of Hennessey, Oklahoma. While pitching for the Hennessey Sluggers back in the summer of 1909, ole Carl beat the Alton Wholesale Grocery Company team from Enid by a score of 10-4. Seventy two hot summers later, I show up in Hennessey and beat their American Legion Team while pitching for Cobb Creek Legion (CCL) based out of Eakly, Oklahoma. While I could have given up twenty one runs that day and still won by one, I only gave up one and won by twenty one. This particular contest existing as a reflection of a team with ability to score runs and play great defense.

From this common pitcher's mound ground, it becomes obvious there are major league differences in our life paths. Carl became a two hundred seven major league baseball (MLB) career game winner while I learned how to read and write about such great feats. Carl played fifteen years in the MLB while I learned how to read and write about such great feats. Carl won three MLB World Series games while I learned to how read and write about such great feats. Carl Mays played with, and at the talent level of, Babe Ruth while I learned how to read and write about such great feats.

Research of the Hennessey Clipper and the Post-Democrat newspapers from this era confirm Mays won at least five games during his brief Hennessey Slugger career. Highlights include a first game shutout victory for Mays against Douglas on Sunday, August 5, 1909. The Clipper noted "the entire Douglas team were at the mercy of Mays, who did the twirling for Hennessey. Mays proved good and has signed a contract with the Sluggers for the balance of the season, which means from now on, it will be all to win and none to lose with Hennessey." The Press-Democrat noted "Mays, who pitched for Hennessey, had the Douglas visitors on his list from the start and secured a total of twelve strikeouts" in a 10-0 win.

Mays' second game pitched for the Sluggers wasn't as dominant but a 11-4 victory over Drummond none-the-less. As reported in the Hennessey Clipper on Sunday, August 22, 1909, "the Sluggers, and about a dozen good rooting fans, took the Sunday morning passenger to Waukomis where carriages were awaiting them and drove across the country to the little city of Drummond." Mays struck out seven batters as the Sluggers avenged an early season home loss.

The previously mentioned Enid victory came as Mays' third trip to the mound for the Sluggers. Mays compiled a brief season high eleven strikeouts against Enid at Hennessey's Sportsman Park on August 29, 1909.

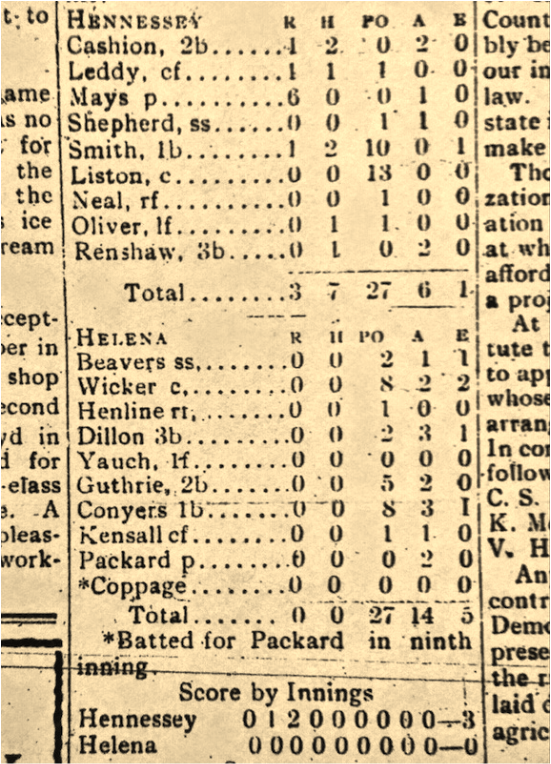

Wasn't but a week later on September 5, 1909, that Mays almost tossed a perfect game for the Sluggers against Helena. This particular game was the first of the season ending Amateur Championship Tournament held in Enid. The 3-0 Hennessey victory was highlighted by the no-hit pitching of Mays. Ironically, it was an eighth inning throwing error by Mays that kept his game from being perfect. On this same day, Mays pitched the second game of the tournament and again defeated Drummond for his fifth and final victory of Hennessey's 1909 base ball season.

After recently visiting the newly opened Carl Mays Exhibit at the Chisholm Trail Museum in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, my interest in his story seemed to skyrocket to a new level. I love baseball and its history more so than keeping up with today's modern game itself. Probably because I'm old and can't play anymore. But, none-the-less, I enjoy delving into baseball history with the same level of enthusiasm that comes from those old playin' days.

During my visit, I ask Chisholm Trail Museum Director Adam Lynn about the early days of Mays' youth in and around the Kingfisher and Hennessey areas. I also asked how Mays came about learning the game of baseball while his family resided in rural Kingfisher. I think we will all enjoy Adam's passionate replies found within this particular blogUmentary.

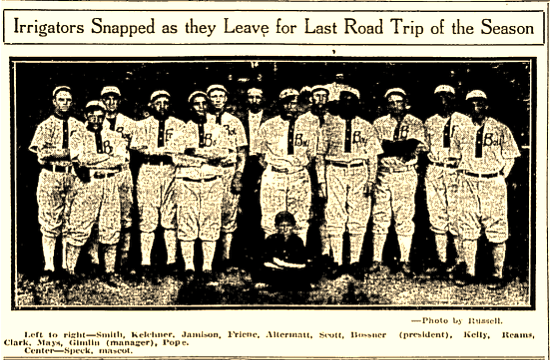

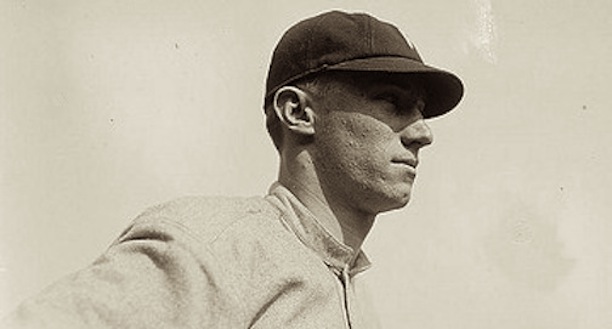

It took some neck deep net searching to piece together Mays' trail from the Hennessey Sluggers to the big leagues with Boston's Red Sox. In 1912, Carl was found up in the greater northwest pitching for the Boise (Idaho) Irrigators of the Western Tri-State League. Carl clocked in a record of 22 wins and 9 losses for the Irrigators.

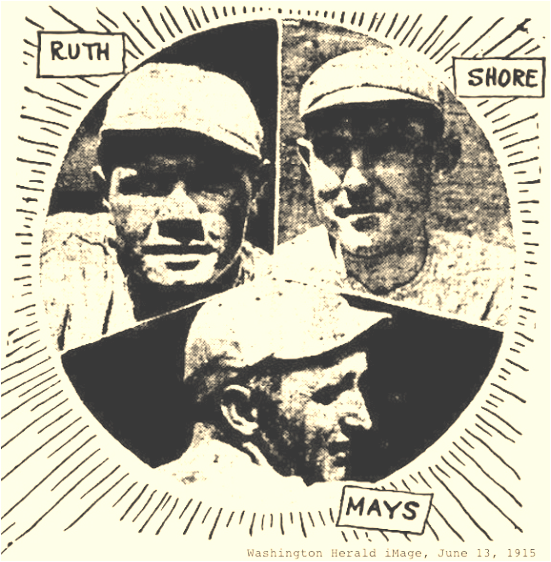

From Boise City and in 1913, Mays migrated even farther west and pitched for the Portland Colts of the, who would have guessed, Northwest League. Although his earned run average (E.R.A.) was at a decent 2.45 for the Class B Colts, he only won ten games but batted a nice .364 with a walk off home run against crosstown rival and Double A level Portland Beavers. From there, Mays made his way to the east coast and hooked up with his career long pal Babe Ruth who both starred for the Providence Grays in 1914 before moving on to the bigs with the Sox in 1915.

Researching highlights from Mays' early major league career, I discovered he had become a top rated submariner for the Boston Red Sox by 1917. He won a total of 22 games with The Baseball Chronicle recognizing a league leading 1.74 E.R.A. In a year when baseball great Ty Cobb was performing at his standard batting championship level, the young guns of Carl Mays and Babe Ruth were beginning to make their own championship noise.

It was very interesting to unearth news of one particular and dramatic incident from the 1915 season. It included the one they call Tyrus "Ty" Cobb tossing a bat towards a rookie year pitcher Carl Mays with a most stormy relationship being born in baseball. "Cobb is the greatest ball player in the world and also the dirtiest," said Mays in the November 30, 1915, edition of the Grand Forks Daily Herald.

Following this potentially lethal bat tossing towards Mays by Cobb, Red Sox shortstop Everett Scott "picked it up and brought it in and I walked back to Cobb and shoved it out at him. Just as he reached for it I pulled it back," shared Mays. "Again I stuck it out at him, and when he reached for it this time I let it fall to the ground. For a minute or two he refused to pick it up, but then did so when the umpire ordered," added Mays. "Cobb tries to get the goat of every young pitcher. If a look or hot words could have killed me, I would be inhabiting a wooden kimono now."

Makes a person wonder if Mays' courageous ability, as a rookie, to stand up to the world renowned nastiness of Ty Cobb was the birth place of his own unpleasant public persona? If that's the case, seems a man would need room to do what he's gotta do to survive within such a distressed environment of baseball times.

On August 30th of 1918, Mays gave up only one run while earning both victories in a Red Sox doubleheader sweep. Mays was also the winning pitcher in two World Series games for the Red Sox in 1918. He beat the Cubs 2-1 in game six to close out a triumphant series for Boston. At the time, who could have known it would be ninety six more years before the Red Sox would win another one?

On August 16th of 1920, Mays, now pitching for the Yankees at New York's hallowed Polo Grounds, reared back and threw the infamous pitch that hit Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman in the head. Chapman died from this impact the next day.

With consideration of it is what it is and a magnificent baseball story now dazed with paramount catastrophe, a genuine private investigator such as Jim Rockford would have to ask the hard questions. Same as I did of Adam Lynn and his thoughts about this tragic incident that tainted the otherwise fabulous career of Carl Mays.

Where do we go from this tragic death blow to professional baseball time stamped and paralleled with the breaking news of Chicago's infamous 1919 Black Sox scandal? As I dug deeper into The Baseball Chronicle, I found a "to-his-dying-day" statement from Carl Mays. Mays insisted that "the pitch that killed Chapman would have been called a strike had he managed to duck out of the way." Chapman was historically noted for hugging the plate so closely when batting that his head was usually in the strike zone.

Like any pitcher worth a grain of salt, golden aged or modern day, the plate belongs to us mentality rules the standard mind set. Was this disastrous death toll event within the world of professional baseball so shocking that everyone seemed to literally dismiss the fact that it could have been and was an accident? A good lawyer such as Beth Davenport would argue that if a pitcher is supposed to throw a strike and the batter's head is in the strike zone, who is truly at fault? We can all join a ghost jury of that era and make judgement for ourselves.

Furthermore, and despite my great grandfather being smart enough to wear a helmet in World War I, baseball leadership seemed to possess no inclination or proactive thoughts about head protection or batter safety in 1920 when Chapman was struck and killed. This, even after a minor league batter, Mobile (Alabama) Sea Gull John Dodge, was struck in the head and killed in a Southern Association League game four years earlier in 1916. Dodge and Chapman are the only professional players known to have died from being hit by a pitch. Chapman being the only one in the major leagues.

We do have to wonder if the U.S. Army can foresee the great need of head protection, and, considering baseball had already incurred such a devastating death blow to the head, why then, at the least, were some protective measures not already in place when Ray Chapman stuck his noggin out over the plate and died in 1920? Although Frank Mogridge was granted a patent (#780899) for a "head protector" in 1905, batter safety was pretty much ignored for the next fifty five years. Although Hall Of Famer Roger Bresnahan developed a "leather-batting" helmet in 1908 after being struck in the head and severely injured, batter safety was pretty much ignored for the next fifty two years.

Ironically from the point of Chapman's death blow in 1920, it took baseball governorship near forty more years to even seriously begin to think about this problem. Headgear and helmets did not truly come into play in the major leagues until 1960 when Jim Lemon became the first player to wear a "little league" helmet in a major league game.

So I ask, why is Carl Mays, to this day, held personally responsible for what is clearly the fault of uncontrollable circumstances of his time. A batter who crowds the plate with his head attached to the strike zone and leadership that did not care if said batter wore head protection or not. Again, I ask who is at fault?

I rest my case and hope that Carl Mays will someday be recognized more for his on-the-field accomplishments and not just for the fatal accident that has made him so infamous. Two hundred and seven major league victories is nothing to sneeze at. A World Series victory is what all pitchers dream about much less than the three earned by Carl Mays. Although he carried a harsh persona that could endure and subdue the ferocious testings of Ty Cobb, I find it most hard to believe he would have or could have killed a man on purpose.

The contest between the Yankees and Indians on August 16, 1920, was a baseball game not a war. It just doesn't seem there would be room for a death wish mentality from anyone involved. Yet, that undeserved death blow perception lives on in Carl Mays' infamy some ninety five years later as we are afforded an opportunity to look at his career in exhibit form.

Museum Director Adam Lynn shares some of the more enjoyable elements that can be experienced as a visitor to the museum's Carl Mays Exhibit.

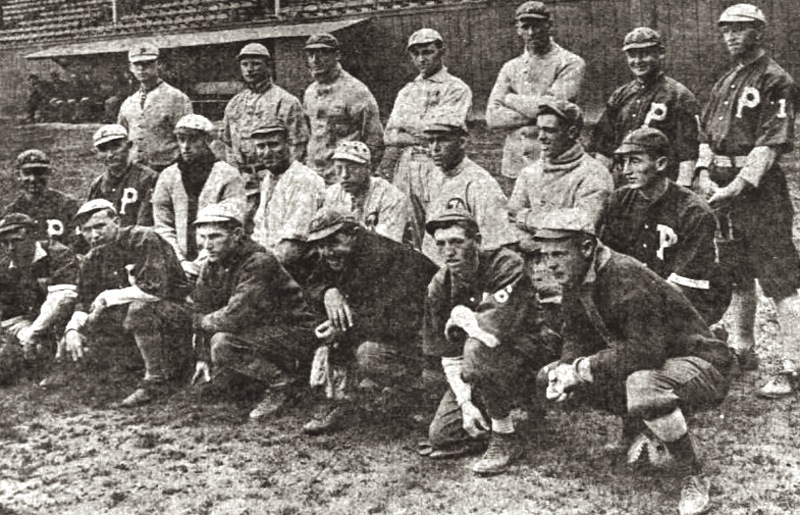

What an interesting and historical baseball story it is. The exhibit itself includes some very nice pieces that represent Mays' history. From baseball cards to newspaper articles to enlarged images as well as time stamped replica uniforms, gloves, bats, balls and other equipment.

It is somewhat sad that such a great baseball career is lost within one pitch within one game. Certainly unanswered questions remain almost a full century later. Did Carl Mays do it on purpose? Was Ray Chapman's head in the strike zone? Does Carl Mays belong in the Hall Of Fame? Would he already be in if not for the one dreadful pitch? Like all of us, Adam Lynn carries his own opinion about the incident and the MLB Hall Of Fame viability of one Carl Mays. Before I concluded my visit and left town, he shared some final thoughts relative to these matters.

Although devastating at the time, Carl Mays was able to rebound from such calamity and concluded his career with remarkable success. In 1921, The Baseball Chronicle noted that Mays was the workhorse of the New York Yankee pitching staff as he won a league leading twenty seven games to go along with seven saves. Despite being exiled to the bullpen in 1923, Mays set a record by defeating the Philadelphia Athletics for a 23rd straight time. After being released by the Yankees, Mays came back strong with a twenty win season for the Cincinnati Reds in 1924. Two years later in 1926, he won another nineteen games for the Reds while leading the league with twenty six complete games pitched. After this successful 1926 season, Mays only won fourteen more games to boost his career total to two hundred seven and was out of the professional baseball ranks by 1929.

Author's Note: Except where indicated, all iMages are part of the Chisholm Trail Museum Exhibit.